How did we get here? The making of Minnesota’s highly developed economy.

Join us for the report release on May 11!

Seeds of future growth were scattered across Minnesota’s economy in the mid-1950s.

In 1955, a new startup named Polaris Industries built a first-of-its-kind snowmobile in Roseau, Minnesota, positioning the young company to capitalize on a growing market for recreational products in post-war America. Meanwhile, 240 miles east of Roseau, the Reserve Mining Company in Babbit shipped the state’s first load of taconite on Lake Superior, marking a new phase of iron-ore mining in Minnesota.

That same year, a young physician, Paul Ellwood – who had recently moved to Minneapolis from southern California – converted a University of Minnesota polio hospital into a rehabilitation center and started analyzing the distorted incentive structures in healthcare. Over the next several years, he would devote his full attention to treating the healthcare system rather than just treating patients. His new model of health maintenance organizations would provide the foundation for the formation of a new company called United HealthCare Corporation just two decades later.

Then in 1957, a small group of engineers and managers from the St. Paul division of Sperry-Univac left to form a new venture focused on building powerful mainframe computers. Their new company, Control Data Corporation, would emerge as a market leader in the computing industry and help establish Minnesota’s first cluster of high-tech electronics firms.

Out of this budding ecosystem of electrical engineering also came a young University of Minnesota student, Earl Bakken, who in 1957 created the first battery-powered pacemaker in a Northeast Minneapolis garage; and, upon its success, eventually founded Minnesota’s most iconic medical device business of Medtronic.

The stories go on. Ecolab went public in 1957, further establishing itself as a global leader in chemicals manufacturing. Dayton’s – a long-standing fixture in the Minneapolis retail scene – expanded to the growing suburb of Edina in 1956 and built the first fully encapsulated indoor mall in America. Across Minnesota, entrepreneurs were introducing new ideas and products to meet a fast-growing consumer market in the U.S and around the world.

Over the following four decades of the 20th century, Minnesota completed its remarkable transition from a largely commodity-based economy to a highly developed knowledge-based economy with leading industries, high innovation rates, above-average per capita incomes, and the largest concentration of Fortune 500 companies in the United States.

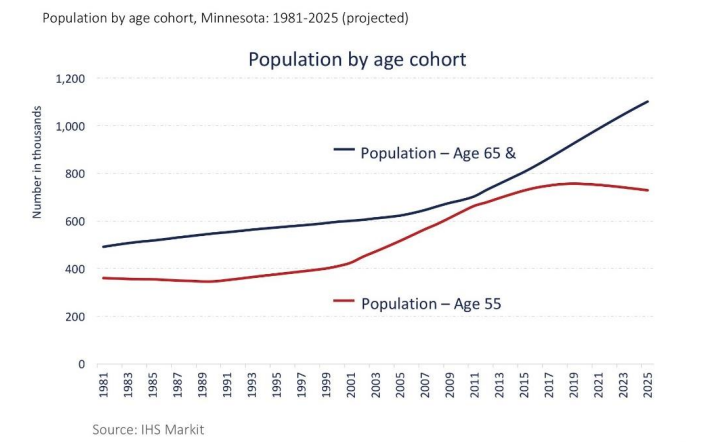

Supporting this economic transition was a steadily growing population and educated workforce that supplied the talent and capacity to turn great ideas into great companies. Minnesota’s population swelled by nearly 1.5 million people between 1950 and 2000, and its labor force grew by an average annual rate of 2% between 1977 and 2000.

Minnesota’s economy outpaced growth in the Midwest and U.S. in the last three decades of the century. Real GDP grew at a robust pace of 3.4% annually from 1977-1997, with growth accelerating particularly fast in the 1990s as personal computer and internet technologies boosted productivity rates. Minnesota experienced faster job growth than the U.S. economy in 22 of 30 years between 1970-1999. Per capita income grew faster in Minnesota and reached 106% of U.S. levels by the end of the century, leaving Minnesota more prosperous than any state in the region.

However, demographic changes were altering Minnesota’s economic outlook. The four million babies born in 1955 in the U.S. would turn forty-five in the year 2000, and by 2020 would reach the retirement-age of 65 years old. Slowing birth rates in Minnesota and throughout the U.S. meant a smaller cohort of Gen X’ers and Millennials would be available to fill the jobs left vacant by the Baby Boomer generation.

Industry changes and migration patterns altered the economic landscape as well. The emergence of digital technologies in the 1990s and the shift of employment from industrial to service-based industries was changing the types of skills and education that workers needed to succeed in the new economy. And the steady advance of urbanization was starting to hinder the ability of rural communities to sustain their local economies.

These shifting realities were not lost on planners and leaders in Minnesota. The Citizens League, a St. Paul-based think tank, published a series of reports in 1998 and 1999 documenting the implications of these demographic and industry changes on the state’s economy. They exhorted Minnesota policymakers, educational institutions, and state agencies to prepare for these changes and refocus from job creation to job skills and productivity as the primary goals of state economic policy.

Slowing growth in the 2000s

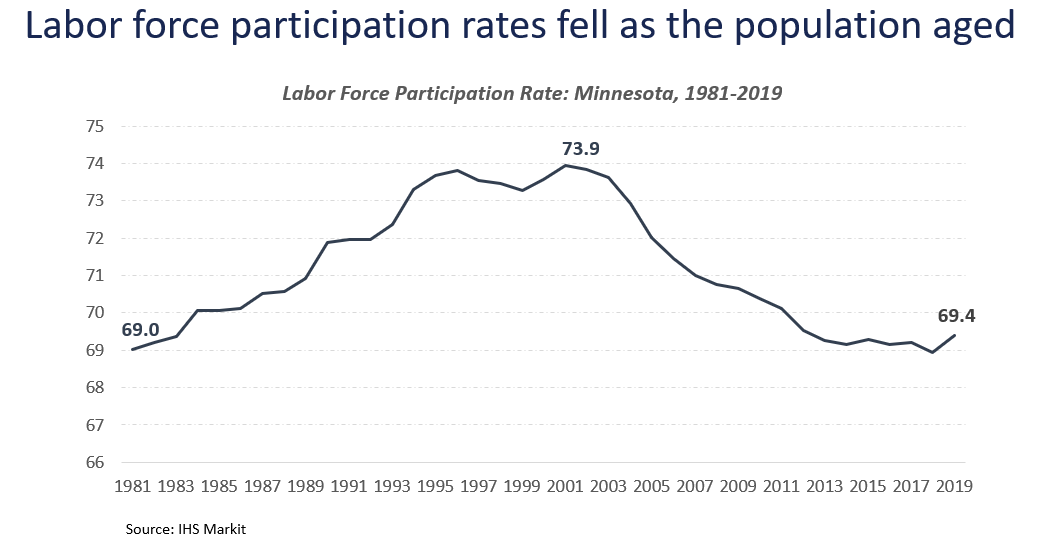

Slowing population and labor force growth came as expected. Minnesota’s total labor force growth slowed from an average annual rate of 1.7% in the 1990s to just 0.5% in the next decade and 0.6% in the 2010s. Labor force participation rates fell as the population aged, declining from a peak of 73.8% in 2001 to 69.4% by 2019. On top of that, Minnesota’s net domestic migration flipped from positive to negative after 2000 and remained negative for 15 consecutive years, exacerbating the state’s workforce challenges.

Yet, attention to these long-term trends was displaced by short-term challenges brought about by the 2001 recession and subsequent Great Recession in 2007, which displaced thousands of workers and led to a period of high unemployment. While Minnesota experienced a record-low unemployment rate of 2.5% in 1999, the state’s unemployment rate averaged 5.4% from 2002 – 2013. This inevitably led to a shift in focus back to job creation and aid to jobless workers.

As Minnesota gradually recovered from the impacts of the Great Recession, slow labor force growth became more apparent, and the issue of workforce availability again loomed larger in the state’s economic priorities.

The combination of demographic factors and two recessions led to a period of low economic growth in the state. Minnesota’s real GDP slowed to just 1.7% annual growth from 2000-2019, down from 4.1% in the previous decade. Job growth slowed even further to just 0.7% and trailed U.S. job growth in 13 of 20 years. Minnesota ended 2019 with a highly developed but slow-growing economy and an uncertain path forward.

Minnesota 2030 – A Framework for Economic Growth

The Minnesota Chamber Foundation identified a need to provide more clarity surrounding Minnesota’s future. In 2019, the Minnesota Chamber Foundation launched research into its first report on Minnesota’s economy – its past performance, and drivers of its future. No one could have predicted the global health crisis and economic upheaval that was about to unfold.

The first Minnesota: 2030 report was released in May of 2021, amid economic recovery and wavering uncertainty about the path ahead for Minnesota and the country.

Minnesota: 2030 provided a guidepost on the economy and recommended a framework for growth. Three actionable strategies to accelerate and strengthen Minnesota’s economy:

- Build on strengths: Further develop Minnesota’s diverse economic strengths while accelerating key growth areas, such as technology and health care.

- Leverage Minnesotans: Beat labor force projections and equip Minnesotans with the skills needed to succeed in a changing economy.

- Strengthen communities: Help communities thrive by strengthening core assets — housing, child care, connectivity — and embracing all Minnesotans, making workforce inclusion a strength.

The report provides a ten-year outlook for Minnesota’s economy. As such, the Minnesota Chamber Foundation will provide timely updates on economic performance and most importantly, progress on the recommendations to strengthen Minnesota’s competitive position in the Midwest, the country and around the globe.

In May 2023, the Minnesota Chamber Foundation will release an update to its Minnesota: 2030 report. The report will provide an in-depth analysis of Minnesota’s economic performance since the pandemic and revised economic forecasts. The report builds on our original recommendations for growth and highlights some priority strategies moving forward.

Look for the Minnesota: 2030 – 2023 Economic Snapshot this spring and join us in Minneapolis on May 11 to hear more about our findings.

Interested in the report release?

Join us on May 11 as we examine the performance of today’s economy, and a look toward 2030. Hear from business leaders on their strategies to invest in people and innovation to advance productivity to accelerate their company’s growth, and that of Minnesota’s economy.