Minnesota: 2030 | 2023 edition - Minnesota’s economic performance 2020–2023

Minnesota’s economic

performance 2020–2023

Few could have envisioned the circumstances that would come to dominate the economic landscape of the early 2020s. The state’s unemployment rate sat at 3.3% in December 2019, and tight labor markets slowed job growth in the second half of the 2010s, creating questions about Minnesota’s capacity for future economic growth. A Wall Street Journal headline from October 2019 read, “Minnesota, Long a Bright Economic Star, Wonders What’s Next,” highlighting case studies of hiring challenges among employers and stagnating labor market activity.

By March 2020, however, Minnesota’s economy was upended by the global COVID-19 pandemic that halted economic activity and led to the worst public health crisis in a century.

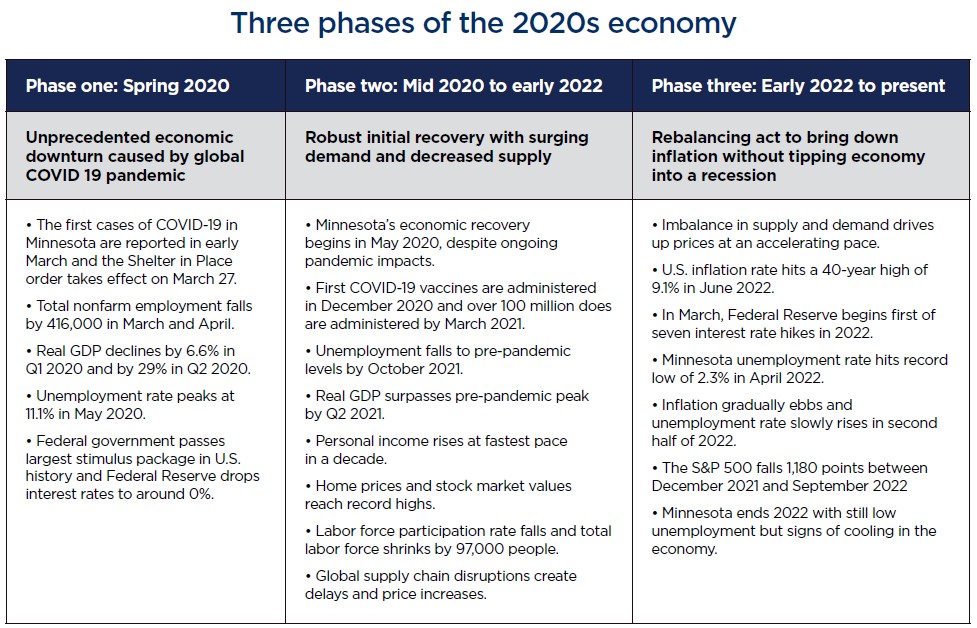

Three distinct phases have marked the 2020s economy:

1. The unprecedented economic downturn in the spring of 2020.

2. The extraordinary response and initial recovery from this downturn.

3. The imbalances in supply and demand that led to a sharp rise in inflation and an aggressive monetary response to slow prices without sparking a recession.

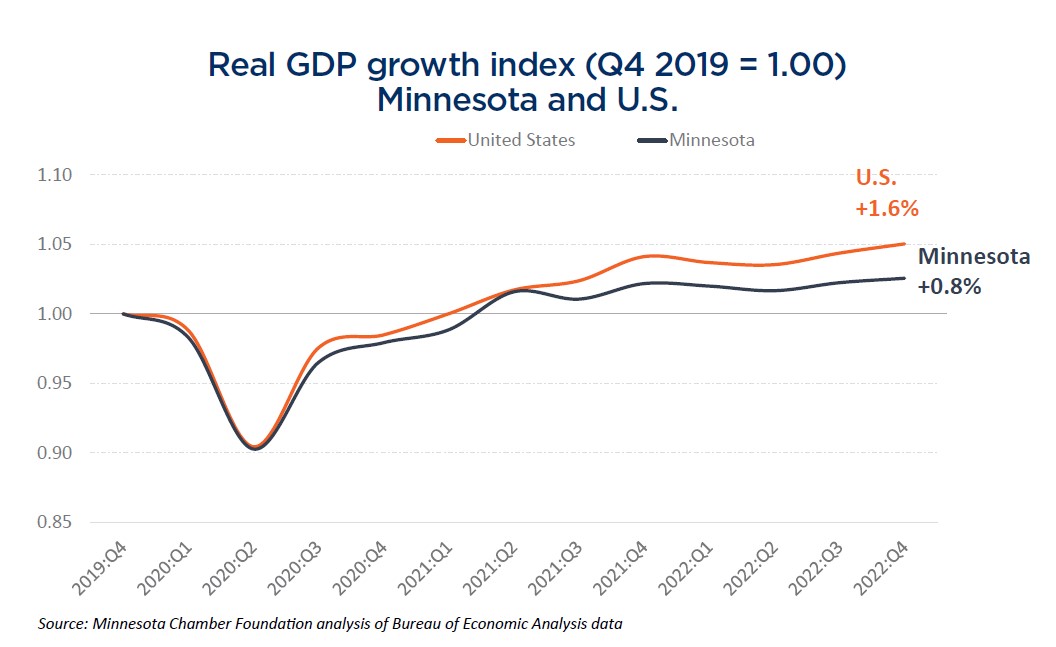

Further, while Minnesota largely followed the direction of the U.S. economy so far this decade, the state recovered and grew at just half the rate of the U.S. and ranked in the bottom 20 states across most major economic growth indicators. The unique circumstances of the past three years created new questions about economic competitiveness among states, as remote work and a resurgence of large-scale U.S. industrial policy created new opportunities and threats for state economies.

Finally, these changes created a mix of economic outcomes across industries and regions of the state since 2020. The following section outlines key trends and markers of economic change in the first three years of the decade.

The 2020 recession was the deepest on

state record but was short-lived, with

Minnesota’s GDP and unemployment

recovering by the summer and fall of 2021.

Economic downturn and initial response

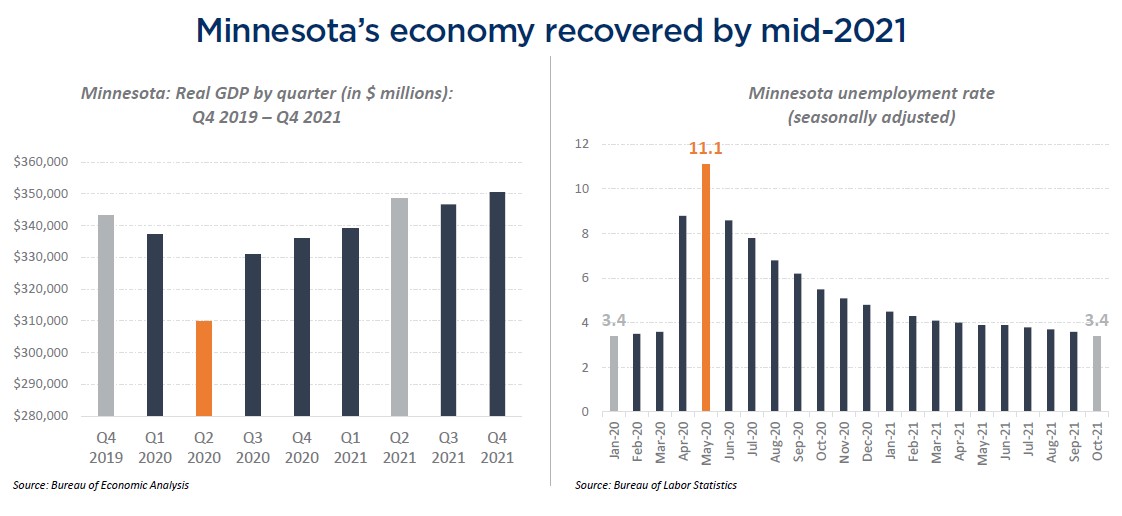

Minnesota experienced an unprecedented economic downturn in the first quarter of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic halted economic activity in Minnesota and worldwide. Total nonfarm employment fell by 416,000 jobs in March and April, an amount larger than the entirety of North Dakota’s workforce. Unemployment spiked to 11% in May. State GDP declined by nearly 30% in the second quarter. Tens of thousands of businesses around the state were forced to close their doors and either pivot to remote operations or temporarily close their business altogether. All indicators showed that the economic fallout experienced in late March and April of 2020 had hit with the magnitude of the Great Depression and the suddenness of a natural disaster.

The scale and speed of the 2020 downturn were matched by an aggressive federal response to provide relief to businesses and households. Within the first year of the pandemic, Congress authorized roughly $5.5 trillion in economic relief, and the Federal Reserve enacted stimulative monetary measures to increase capital availability. Federal measures to stabilize the economy combined with a rapid shift among employers and workers to adapt to new realities enabled a robust initial recovery through the second half of 2020. By the end of 2020, Minnesota recovered nearly 180,000 of the initial jobs lost that spring, GDP bounced back by 30.5% in Q3 and 6% in Q4, and unemployment ebbed to 4.8%.

Further, the mass deployment of resources to rapidly develop COVID-19 vaccines reached a critical turning point. By December 2020, the first COVID-19 vaccines were delivered, and by March 2021, over 100 million doses had been administered to the U.S. population. This helped create the conditions for economic recovery to accelerate faster in 2021.

Surging demand in 2021

Minnesota, like the U.S. economy, experienced a surge in consumer demand, as personal income grew at the fastest rate in a decade and asset prices – including housing and stock market values – soared to new highs. The mix of consumer spending also shifted early in the pandemic from local services to goods and digital technology sectors, as households spent more time at home and online. Growth in these sectors continued to accelerate in 2021, even as the economy reopened and many in-person activities resumed.

By the summer and fall of 2021, Minnesota’s economy had, by several key measures, fully recovered from the largest downturn in the state’s modern history.

The state’s real GDP surpassed its pre-pandemic peak in the second quarter of 2021. The unemployment rate, which peaked at 11% in May 2020, fell to pre-pandemic levels in October 2021. The notable exception to this recovery, however, was the lack of recovery in total employment. While the unemployment rate returned to pre-pandemic levels by October, Minnesota’s economy still had 108,800 fewer nonfarm payroll jobs than it did at the beginning of 2020. What accounted for this apparent contradiction?

The pandemic-recovery period has been

marked by supply-side shocks, reflected by

a historic shortage of workers, supply chain

disruptions and rising inflation.

Workforce shortages

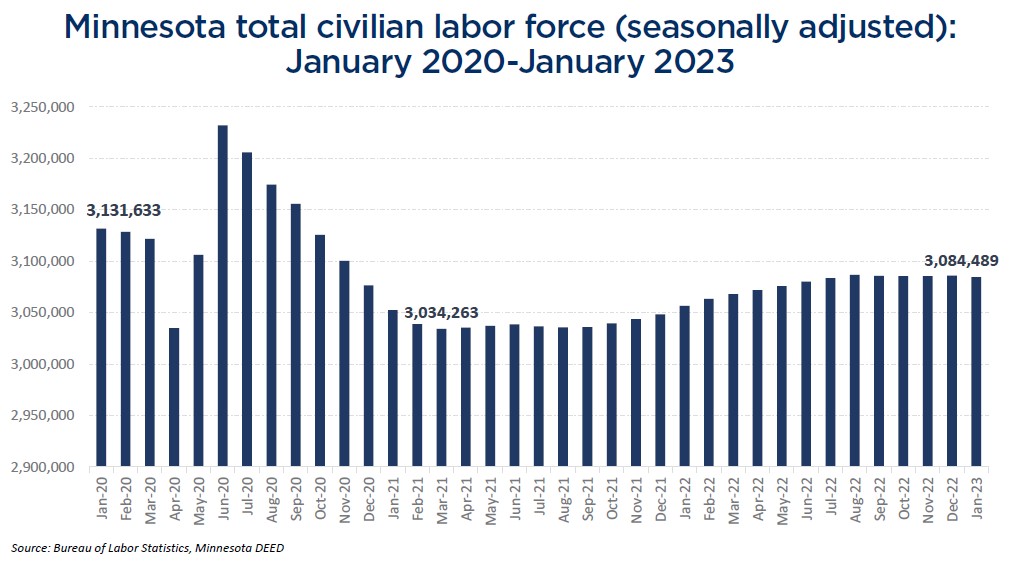

As consumer spending and output rose throughout 2021, so did demand for workers. Minnesota’s job opening rate more than doubled from December 2019 to December 2021. However, despite strong labor demand, supply in the labor market moved in the other direction.

Minnesota’s total available labor force declined by over 97,000 people in the first twelve months of the pandemic. Likewise, Minnesota’s labor force participation rate fell from 70% in January 2020 to 67.3% by September 2021. Though it is difficult to precisely measure the causes of this decline, many economists point to a combination of early retirements, COVID-19 health impacts and lack of child care availability as leading factors that played a role in this sudden and steep decline in workers.

Whatever the exact combination of causes, the imbalance of supply and demand in the labor market drove unemployment to historic lows. By January 2022, Minnesota’s unemployment rate fell below 3% and hit a record low of 2.3% in April 2022. This presented both a strength and challenge for Minnesota’s economy, as tight labor markets meant fewer unemployed workers but less capacity for employers to add jobs and meet growing demand.

Supply chain disruptions

In addition to historic workforce shortages, the early 2020s have been impacted by a shock to global supply chains. Supply chain disruptions occurred early in the pandemic and continued to distort economic activity over the next two years, creating bottlenecks, shipping delays and steep price increases in everything from electronics and building materials to food and energy. These disruptions stemmed from both supply-side constraints on global production and transportation of goods as well as demand-side pressures as consumer spending shifted from services to goods. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022 further disrupted global supply chains and placed new obstacles to the flow of energy, food and other goods in Europe and around the world.

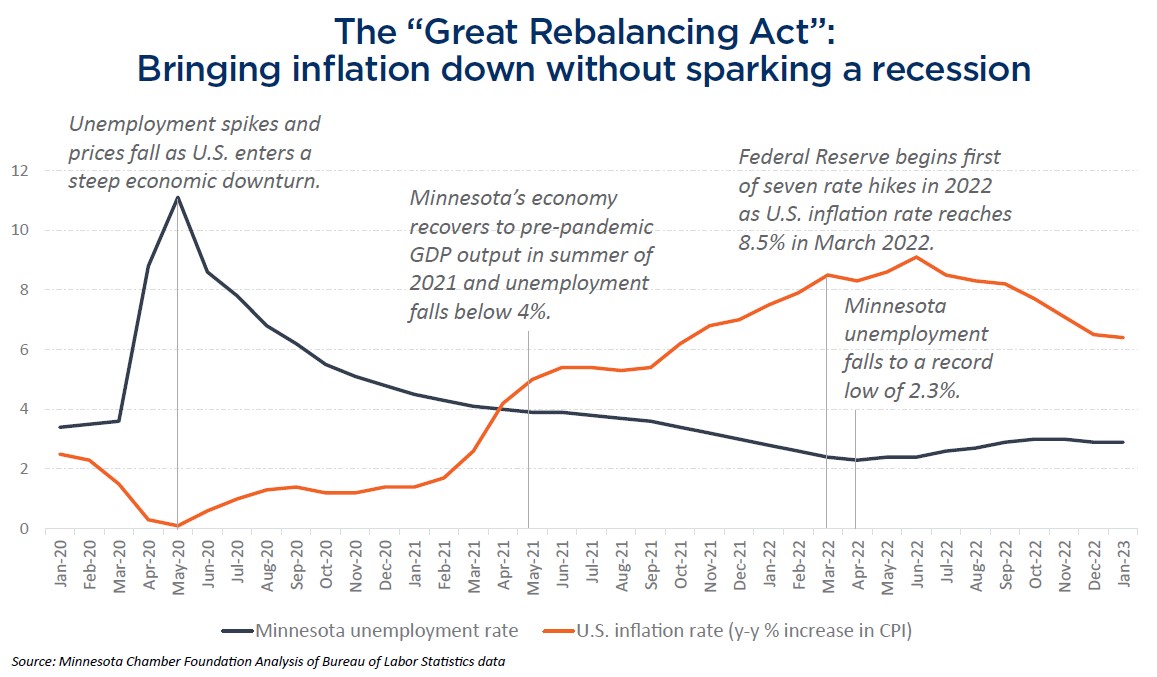

Inflation and interest rates

U.S. inflation held at historically low rates throughout the 2010s, with year-over-year increases in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) averaging just 1.6% in the decade following the Great Recession.

The pandemic and ensuing recovery changed this, however. By early 2021, market imbalances began appearing in the U.S. inflation data. Consumer prices then accelerated at the fastest pace in 40 years, hitting a peak of 9.1% in June 2022. By this time, inflationary pressures had come to dominate economic concerns, fueling uncertainty and squeezing cash flow for businesses and households.

It wasn’t until March of 2022 that the Federal Reserve took its first steps to combat inflation by raising the federal funds rate up from near-zero percent levels. Once it did, however, the Federal Reserve moved aggressively, initiating a series of seven consecutive interest rate hikes in 2022.

This marked the shift into a distinct new phase of the 2020s economy, as monetary objectives to bring down inflation without tipping the economy into a recession seemed to dominate everything else.

Such concerns have shaped expectations and concerns in Minnesota, along with the rest of the nation. As of late 2022, rising interest rates appear to be taking effect. Inflation fell for six consecutive months, and hiring demand cooled. Minnesota’s unemployment rate rose steadily, albeit slowly, from a low point of 2.3% in April to 2.9% in December 2022.

Despite some signs of cooling, Minnesota’s economy remained stable heading into 2023. Real GDP expanded by 1.3% in the fourth quarter of 2022, and employers continued adding jobs, nearing pre-pandemic levels.

While Minnesota largely followed the

national trendline, the state’s economy grew

at just half the rate of the U.S. and ranks in

the bottom 20 states across most major

growth indicators so far this decade.

Minnesota’s economy was subject to large forces beyond its direct control in the first years of the 2020s. No state in the U.S. avoided the health or economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic or was shielded from the effects of rising inflation and interest rates. Yet, economic performance varied widely across states, even within the constraints of these broader forces. As the data make clear, Minnesota consistently trailed the U.S. economy so far this decade and ranked in the bottom twenty states across most major indicators of economic growth.

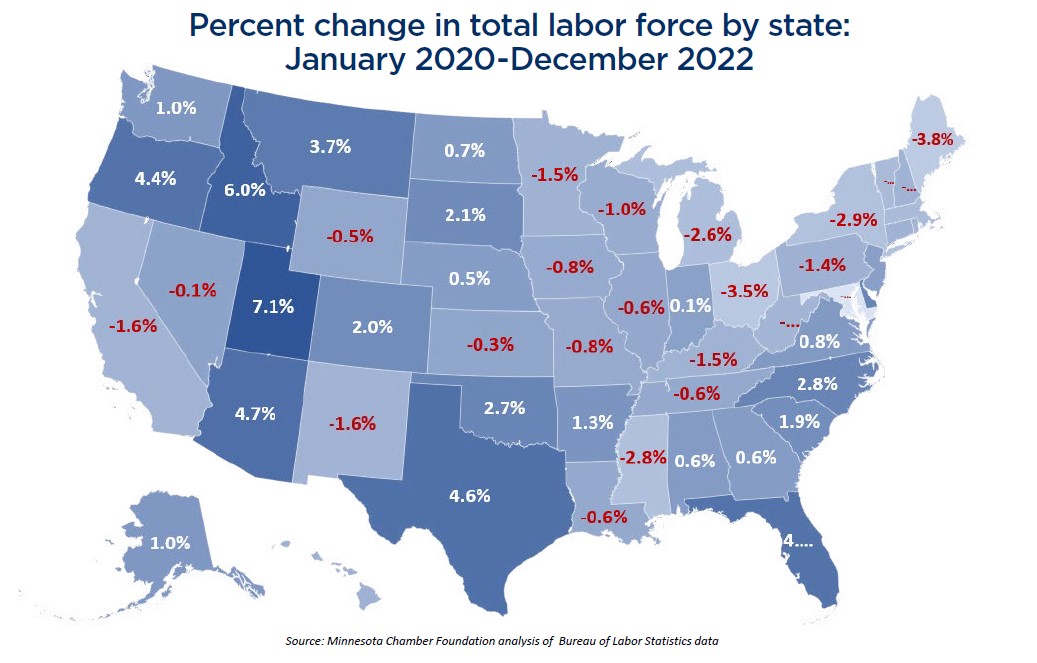

The state’s below-average growth since the beginning of 2020 is linked to its particularly sharp decline in labor availability and its position in the slowest-growing region of the U.S. These same trends were present heading into the decade but were exacerbated by the dynamics of the 2020 downturn and subsequent recovery. Underlying these themes are deeper questions about various factors that influence the state’s competitiveness, such as its tax and regulatory climate, availability of housing and child care, economic development efforts to attract business investment and overall reputational issues.

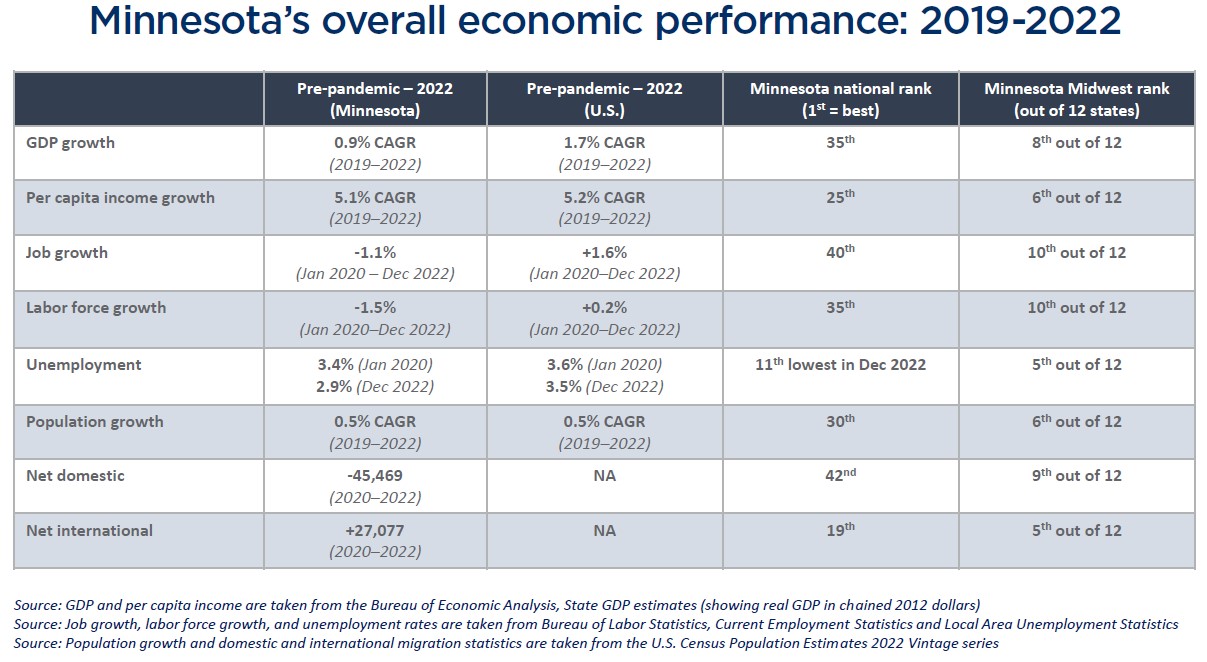

GDP, income and job growth

Minnesota trailed U.S. growth rates in GDP, per capita income and total employment from 2019-2022. These are among three of the broadest measures of overall expansion in the economy, and in all three, Minnesota grew below the U.S. average and ranked in the bottom half of states so far this decade.

Minnesota’s real GDP grew by roughly half the rate of the U.S. economy from 2019-2022, averaging 0.9% annual growth and ranking 35th among all states. Similarly, the state ranked 40th in job growth, with total employment declining 1.1% from 2019-2022, while total employment grew by 1.6% in the U.S. in that time. Per capita income growth fared better, with Minnesota roughly mirroring U.S. per capita income growth and ranking 25th overall.

Two primary factors are linked to Minnesota’s below-average growth in the pandemic-recovery period.

First, Minnesota experienced among the sharpest decline in labor force availability in the U.S. since early 2020, inhibiting businesses’ ability to hire and expand output. Labor force participation rates fell in 2020 and failed to bounce back in large numbers as the economy reopened and hiring demand picked up over the next two years. This left the state with over 47,000 fewer workers in the labor force in December 2022 compared to January 2020, ranking 36th nationally in labor force growth in that time. Analysis from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce shows that Minnesota had only 43 available workers for every 100 job openings in December of 2022, making it the worst workforce shortage in the U.S. By comparison, there were 67 workers for every 100 job openings in the U.S. as-a-whole.

State-to-state migration trends may also play a role in Minnesota’s labor force challenges. After improving in the last years of the 2010s, Minnesota’s net domestic migration fell significantly in the early 2020s, losing nearly 36,000 residents to other states from 2020-2022 and ranking 42nd nationally.

A second explanation for Minnesota’s below-average growth relates to its regional position in the upper Midwest. While Minnesota’s economy has grown slower than most states since 2020, its growth roughly mirrored that of the region. Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that states in the Plains, which includes Minnesota, grew at the slowest rate of all economic regions so far this decade. Real GDP in the Plains region grew at 0.9% from 2019–2022, compared to 2.7% in the Mountain West, which led all regions at that time. This suggests that broader regional factors – such as industry structure, consumer activity, population and labor force dynamics – played a role in the rate of growth in Minnesota’s economy.

Yet, even within the region, Minnesota’s performance has been middling at best. Minnesota’s real GDP growth ranked 5th of seven states within the Plains region since the pre-pandemic peak. Minnesota’s comparative growth within the region follows a longer-term trend. Minnesota’s economy expanded faster than all Midwest states from 1977-1997 and outperformed the region in a variety of economic measures. Since 2000, however, Minnesota dropped to the middle of the pack, growing 6th fastest among the seven plains states and 6th fastest among the 12 states that make up the entirety of the Midwest.

Economic recovery and growth varied

significantly by sector, with tech and

business service sectors driving overall

economic growth.

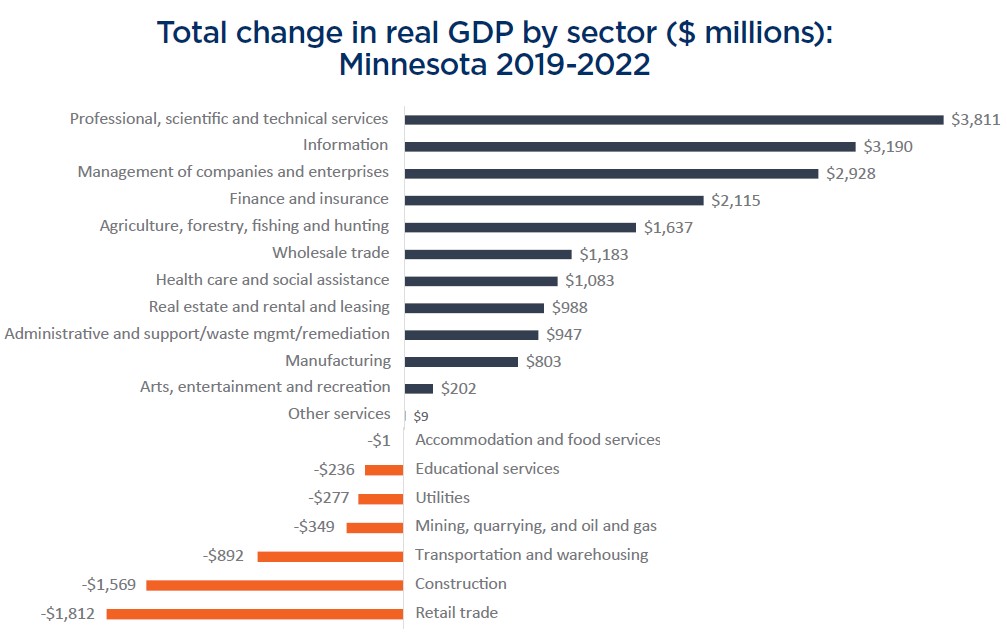

The unusual dynamics of the early 2020s created unforeseen impacts across Minnesota’s industry sectors. Some longer-term trends – such as automation, digitalization and the shift toward knowledge-based service sectors – accelerated during the pandemic and recovery while other industry trends saw a complete reversal. Additionally, sector impacts varied across the different phases of the past three years.

Goods industries: Strong demand in goods industries during the pandemic spurred overall job growth in Minnesota’s manufacturing sector. Likewise, increases in home building and remodeling boosted the state’s construction sector from late 2020 to early 2022. However, rising inflation and a weakening global economy created headwinds in 2022, leading to a cooldown in jobs and output since early 2022 and clouding the near-term outlook for these sectors.

Minnesota’s natural resource industries took divergent paths, with rising commodity prices and high yields boosting farm output. In contrast, Minnesota’s mining and logging sector employment and output fell in the face of headwinds.

Tech, headquarters, professional services, and finance and insurance: Skilled tradable service industries were less impacted by pandemic lockdowns in 2020 and experienced a surge in growth during the pandemic-recovery period. Real GDP growth in four industries – information (composed largely of tech and telecom industries), management of companies and enterprises (e.g., corporate headquarters), professional, scientific and technical services (which includes everything from engineering and law offices to IT service providers and R&D facilities), and finance and insurance – increased by a total of $12 billion between 2019–2022, compared to just $9.8 billion for all other industries combined.

Local service sectors: Local service sectors were among the hardest hit in 2020 and continued to recover from job losses as of late 2022. Yet, differences are apparent within local services as well. Industries offering higher median wages – such as education services, health care, wholesale trade, and transportation and warehousing – surpassed pre-pandemic employment levels by the middle of 2022, while lower-wage industries such as retail and accommodation and food services have yet to fully recover the jobs lost in 2020.

Regional population and economic trends

were disrupted in the early 2020s.

After years of population growth flowing to urban counties, Minnesota experienced a sharp reversal this decade. Population declined in Minnesota’s largest urban counties of Hennepin and Ramsey due to domestic migration losses from 2020-2022. Conversely, population increased in outlying suburban counties and counties with strong recreational and outdoor amenities. While these trends raise new questions about future migration patterns – and the economic implications of those trends – it is too early to tell whether these changes will persist in coming years. Population forecasts continue to show that many Greater Minnesota counties will experience flat or declining populations over the next decade and beyond.

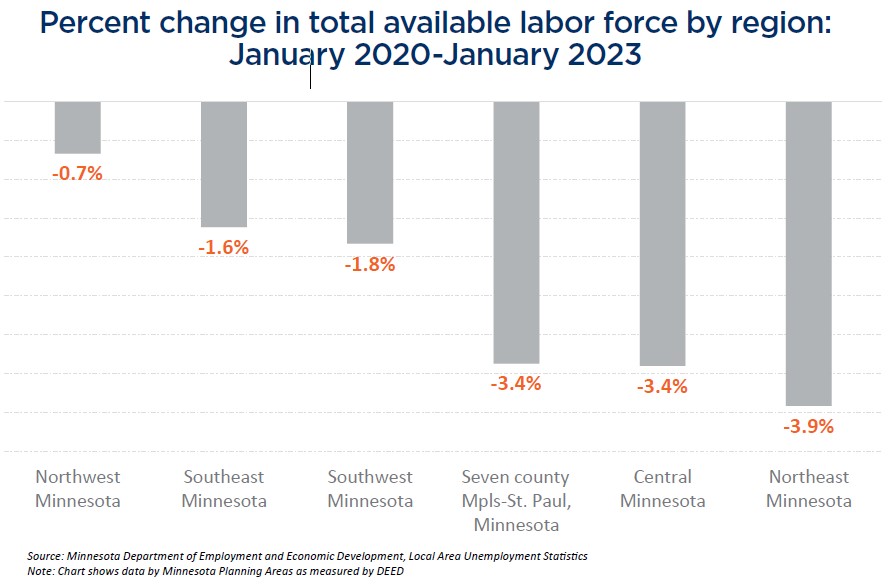

Overall economic performance across regions was mixed. Each regional economy experienced similar directional trends in the first three years of the decade, with all regions experiencing large job losses in early 2020, followed by a recovery period challenged by tight labor markets and workforce shortages. However, the magnitude of these trends varied across regions. For example, Minnesota’s Northeast, Central and Twin Cities regions suffered much larger relative losses in workforce capacity from early 2020 to early 2023, declining by 3.4% - 3.9% in that time. Regional economies in Southern and Northwest Minnesota also saw declining workforce availability but to a lesser extent, declining by a range of 0.7% in Northwest to 1.8% in Southwest Minnesota.